On conformal prediction

What is conformal prediction and why should we care about it?

Introduction

Recently, Ben Recht published a series of blog posts about conformal prediction. I thought they made some interesting points, but really engaging with his critiques requires more than 140 characters and I’m definitely not going to start paying for X.

There was a 'Forbidden' error fetching URL: 'https://twitter.com/jjcherian/status/1756027416655667313'

So as it turns out, the (not so) near future is actually just about six months!

Anyways, you clicked on this link to learn about conformal prediction, so let’s get started by first motivating conformal prediction with a concrete problem. Imagine we’re trying to help a university admissions office admit students who are likely to succeed, so we fit a neural network trained on thousands of historical admissions records and college transcripts to predict a prospective student’s final GPA. The ever-astute admissions officer recognizes, however, that these point predictions are far from perfect. So, she asks “can you give me a range of GPAs that you can guarantee the student is likely to fall in?”

At first glance, this sounds pretty hard! Predicting a range? Providing a guarantee? Those don’t sound like things that neural networks do. But don’t worry, if you hand it some data points that were held-out from neural network training, (split) conformal prediction will solve exactly this task. Given the submitted applications (we’ll denote these by \(X_i\)) and final GPAs (we’ll call these \(Y_i\)) of \(n\) previous students, a conformal predictor makes use of the trained neural network to output a set for the \((n + 1)\)-st prospective student (referred to as \(\hat{C}_n(X_{n + 1})\)) that is guaranteed to contain the true GPA with some user-specified probability \(1 - \alpha\).

\[\Pr(Y_{n + 1} \in \hat{C}_n(X_{n + 1})) \geq 1 - \alpha\]This guarantee is about as clean of a result as you’ll see in statistics. It requires only one assumption: the \((n + 1)\)-st student is drawn i.i.d. from the same distribution as the previous \(n\) students.

So, why isn’t Ben satisfied? He argues that conformal prediction is sweeping two important details under the rug. The guarantee stated above is marginal over both the random data set used to construct \(\hat{C}_n(\cdot)\) as well as the applicant. In plain English, after reading Ben’s blog posts, the admissions officer might ask the following questions:

- Even if the prediction set covers the true GPA with high probability over a random new applicant, could it be terribly inaccurate for this particular student?

- Even if I’m willing to settle for coverage that only holds marginally over a random applicant, what if, by chance, the \(n\) students you used to construct the prediction set were not representative of the applicant population? In that case, how big could the following deviation in the realized coverage possibly be?

The first question relates to a research area sometimes referred to as “conditional” predictive inference. It’ll be the topic of a subsequent blog post.

The second question will be the subject of today’s post, but to come up with a satisfying answer, we’re going to have describe what conformal prediction actually does.

Reframing predictive inference

The explosion of conformal prediction methods in recent years has left most people (including yours truly) a bit confused about what it actually is. So, while I’m sure people may have other ideas, I’ll say here that conformal prediction consists of the following three-step procedure:

- Define some notion of error \(S(X, Y)\) that we’ll call a conformity score

- Estimate the \((1 - \alpha)\) quantile, \(q_{1 - \alpha}\), of the conformity scores that we expect in the future

- Given some \(X_{n + 1}\), define the prediction set to include all \(y\) such that \(S(X_{n + 1}, y) \leq q_{1 - \alpha}\)

This general reframing of the uncertainty quantification problem seems obvious in hindsight, but reducing the problem of estimating prediction sets to estimating the quantile of some test error has been extraordinarily productive.

Most of the research activity in this field consists of improving steps 1 and 2 of this procedure. For example, clever choices of the conformity score can improve the adaptivity and practical utility of the prediction sets issued in step 3. And while the quantile estimation task in step 2 is straightforward under the assumption that future data is exchangeable with the observed data, estimating this quantile under modeled (or even uncertain) distributional shift has produced new methods in causal inference and time series analysis.

Now that we hopefully understand the big picture, we will describe the simplest instantiation of this framework, split conformal prediction (split CP). In split CP, we assume access to a hold-out data set that we use to compute a set of \(n\) conformity scores. To make our lives as easy as possible, we will assume a naive choice for this score, the absolute value of the observed residual, as our running example:

\[S(X_i, Y_i) := |Y_i - f(X_i)|.\]Then, the set \(\hat{C}_n(X_{n + 1})\) is the set of all $y$ such that \(S(X_{n + 1}, y)\) is less than some well-chosen threshold \(q_{1 - \alpha}\). As we alluded to above, split CP transforms the prediction set membership problem into the following quantile estimation problem:

\[\Pr(Y_{n + 1} \in \hat{C}_n(X_{n + 1})) = \Pr(S(X_{n + 1}, Y_{n + 1}) \leq q_{1 - \alpha}) \stackrel{?}{=} 1 - \alpha.\]In split CP, we take \(q_{1 - \alpha}\) to be the \(\frac{\lceil (1 - \alpha) \cdot (n + 1) \rceil}{n}\) quantile of the \(n\) observed conformity scores. Putting all of this together, we define the split CP set as

\[\hat{C}_n(X_{n + 1}) = \left \{y : S(X*{n + 1}, y) \leq \text{Quantile}\left(\frac{\lceil (1 - \alpha) \cdot (n + 1) \rceil}{n}, \{S(X_i, Y_i)\}*{i = 1}^n \right) \right\}.\]Parsing the definition of this prediction set to prove the coverage result above isn’t difficult, but it’s easy to lose the forest for the trees. To understand what’s happening, let’s take a step back and think about what we might have done to construct a prediction set if no one had ever told us about split CP.

Given a good point predictor \(f(\cdot)\), the most natural construction for a prediction set is to add and subtract a constant to the prediction, e.g.,

\[\hat{C}^{naive}_n(X_{n + 1}) = [f(X_{n + 1}) - \epsilon, f(X_{n + 1}) + \epsilon].\]Intuitively, for this prediction set to be valid, we need \(\epsilon\) to be larger than \((1 - \alpha)\)-% of the errors we expect to see on out-of-sample data. Lucky for us, we already obtained a hold-out set that consists of exactly \(n\) such out-of-sample errors. So, the split conformal prediction set estimates exactly this upper bound on \(\epsilon\). So, here’s a naive strategy: what if we just used the empirical \((1 - \alpha)\) quantile of those values? This method for choosing \(\epsilon\) yields a prediction set nearly identical to the split CP \(\hat{C}_n(\cdot)\):

\[\hat{C}^{naive}_n(X_{n + 1}) = [f(X_{n + 1}) - \hat{q}_{1 - \alpha}, f(X_{n + 1}) + \hat{q}_{1 - \alpha}] = \left \{y : S(X_{n + 1}, y) \leq \hat{q}_{1 - \alpha} \right\}.\]Split CP nearly replicates our naive approach: the only difference is a small modification to the empirical quantile. People in machine learning are accustomed to using a hold-out set to estimate the mean test error; here we use a validation set to estimate the quantile of the test error.

At this point, it is important to note that much of the innovation in conformal prediction comes from designing better conformity scores, e.g., using measures of error that have already adapted to the underlying variability of the data. The most prominent example of this is the Conformalized Quantile Regression method of Romano, Patterson, and Cand`{e}s (2020). Instead of defining the conformity score using the residuals of the regression model, they try their best to estimate the quantile of the $Y \mid X$ distribution directly. Still, however, the conformal step consists of making a constant adjustment everywhere.

Debiasing coverage

Split conformal

Now that we have seen and understood the conformal prediction framework in action, I want to return to the second problem our hypothetical admissions officer raised. Recall that while the split CP set delivers \(1 - \alpha\) coverage marginally over the hold-out set, given any particular hold-out set of \(n\) students, the coverage of the resulting prediction set could deviate from this target. Statistically speaking, answering the officer’s question amounts to solving the following problem: how much does the conformal estimate of the \(1 - \alpha\)-quantile of the test conformity score distribution deviation deviate from the true quantile?

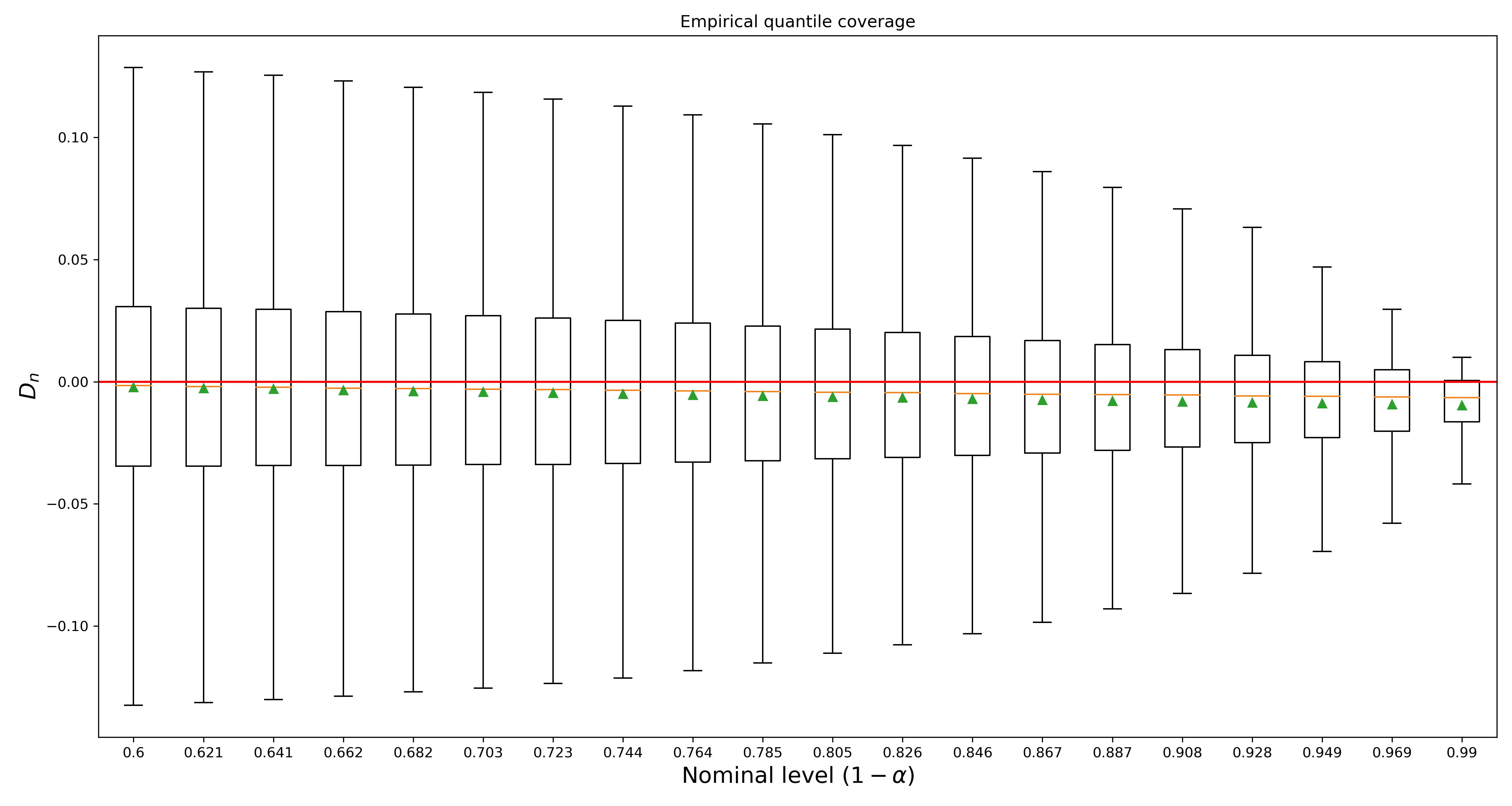

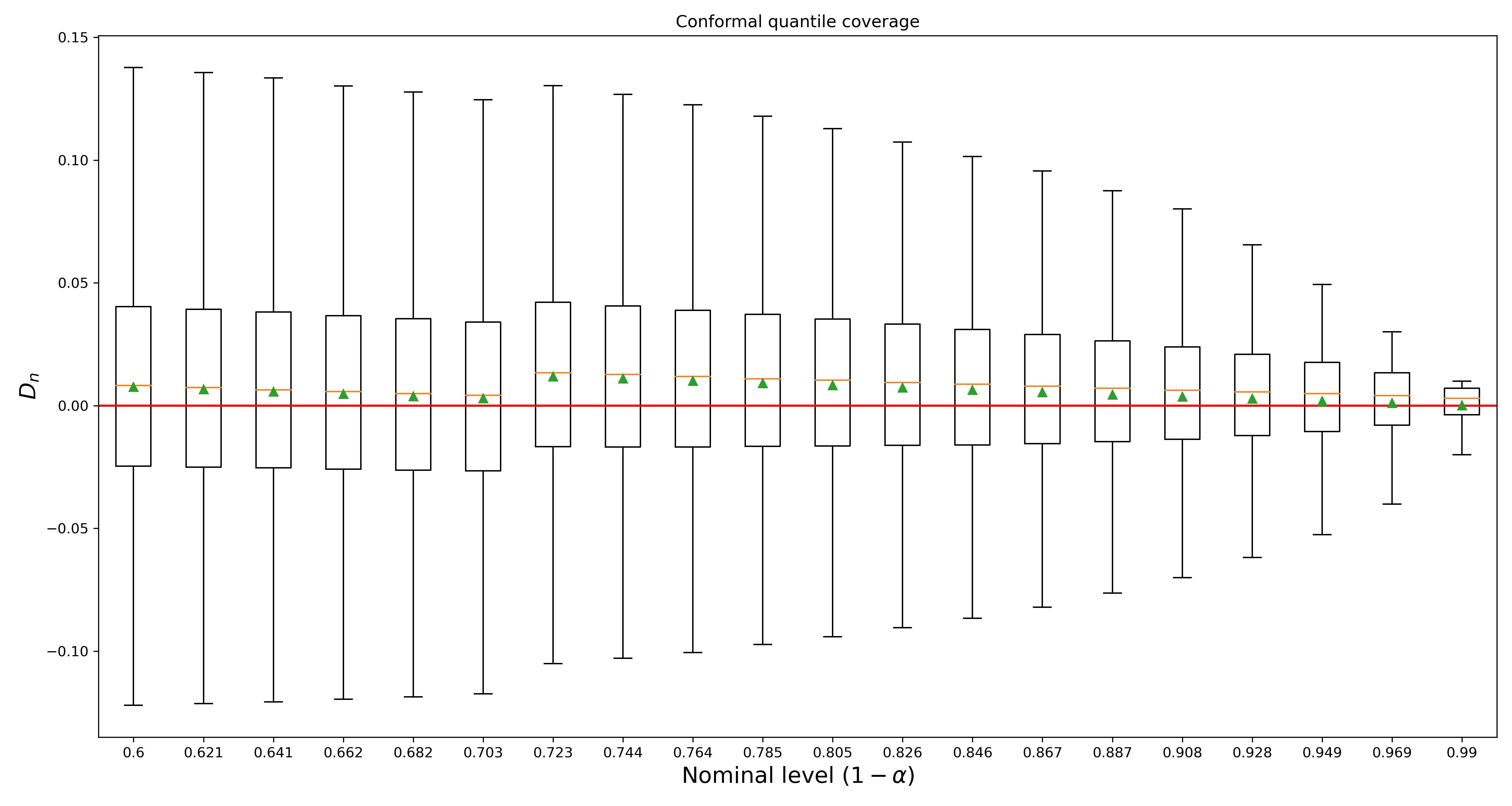

Before we do any math to answer this question, we will run a simulation to get a feel for the result. The results plotted below display the coverage deviation of both the naive quantile estimate and the conformal quantile estimate obtained using a hold-out set of size \(n = 100\). In this toy problem, we will assume that our \(n\) conformity scores come from a standard normal distribution, i.e., \(S(X_i, Y_i) \stackrel{i.i.d.}{\sim} \mathcal{N}(0, 1)\).

The first thing to note that is that the plots above are consistent with the coverage guarantee promised in the introduction of this post. Indeed, for every choice of \(1 - \alpha\), the adjusted quantile from the split conformal prediction set delivers at least \(1 - \alpha\) coverage on average. But this plot also suggests an alternative interpretation of the split CP guarantee that may prove to be more palatable for a skeptic. Rather than providing exact marginal coverage, we might instead say that split CP debiases the coverage of an estimated quantile.

Conformal prediction provides (nearly) unbiased coverage.

OK, so debiasing the coverage guarantee (i.e., shifting all these box plots up a bit) seems like an unambiguously positive thing. But should we really care? Glancing at these results, it’s easy to see that the width of the boxplot is a lot bigger than the gap between the green triangle and the coverage level. Returning to our favorite college admissions officer, she might now ask

- OK, I get that this new split CP interval promises me unbiased (or slightly positively biased) coverage. But what about the deviation \(D_n\) - these boxplots are centered in the right place now, but they’re still so wide! How much should I really care about this?

Indeed, getting to the math, the asymptotics of conformal prediction suggest that bias may not be so important. While the conformal estimate makes an order \(n^{-1}\) adjustment to the naive quantile estimate, the estimator itself only converges at a \(n^{-1/2}\)-rate. Even at \(n = 100\) samples, \(n^{-1/2}\) and \(n^{-1}\) are separated by an order of magnitude (\(0.01\) vs \(0.1\)), so it’s easy to question whether the finite-sample guarantee of conformal prediction is itself missing the forest for the trees.

Click here to know more about the bias

Indeed, some reasonably straightforward asymptotics tell us that whenever \(P\) admits a density, no quantile estimator will obtain coverage that converges at a faster than \(1/\sqrt{n}\) rate to the target. In particular,

\[\sqrt{n} (\Pr(Y_{n + 1} \in \hat{C}_n^{naive}(X_{n + 1}) \mid \hat{C}_n^{naive} ) - (1 - \alpha)) \stackrel{d}{\longrightarrow} \mathcal{N}(0, \alpha \cdot (1 - \alpha)).\]and

\[\sqrt{n} (\Pr(Y_{n + 1} \in \hat{C}_n(X_{n + 1}) \mid \hat{C}_n) - (1 - \alpha)) \stackrel{d}{\longrightarrow} \mathcal{N}(0, \alpha \cdot (1 - \alpha)).\]That is, in the limit of large \(n\), the conformal correction is irrelevant. As a consequence, it’s perhaps incorrect to conclude that we should dismiss concerns about the guarantee being marginal over the hold-out set. Formally speaking, the exact guarantee is obtained via a low-order correction that is dominated by sampling error.

But we don’t have to be satisfied with asymptotic intuition. As it turns out, we can exactly quantify the bias (and variance) of the two quantile estimators we’ve proposed. For simplicity, let’s assume that \(\alpha = \frac{k}{n}\) for some choice of \(k\). Then,

\[\Pr(S(X*{n + 1}, Y*{n + 1}) \leq \hat{q}_{1 - \alpha} \mid \hat{q}_{1 - \alpha} ) = \Pr(S(X*{n + 1}, Y*{n + 1}) \leq S*{(n - k)} \mid S*{(n - k)})\]The latter quantity is drawn from the \(\text{Beta}(n - k, k + 1)\) distribution. The mean of this distribution is the expected coverage, i.e.,

\[\Pr(Y_{n + 1} \in \hat{C}_n^{naive}(X_{n + 1})) = \frac{n - k}{n + 1} = 1 - \frac{k + 1}{n + 1} = 1 - \alpha - \underbrace{\frac{1 - \alpha}{n + 1}}_{\text{undercoverage bias}}\]Recall that the conformal quantile estimator uses the \(\frac{\lceil (1 - \alpha) \cdot (n + 1) \rceil}{n}\) sample quantile, which if \(\alpha < 0.5\) ends up being the \((n - k + 1)\)-st order statistic of the hold-out scores. Thus, the realized coverage is sampled from a \(\text{Beta}(n - k - 1, k)\) distribution, and the expected coverage is

\[\Pr(Y_{n + 1} \in \hat{C}_n(X_{n + 1})) = \frac{n - k + 1}{n + 1} = 1 - \alpha + \underbrace{\frac{\alpha}{n + 1}}_{\text{overcoverage bias}}\]As we can see from the figure, when \(\alpha\) is small and \(n\) isn’t too big, this difference can be meaningful! But when \(n\) is large, a \(\frac{1}{n + 1}\) difference in the expected coverage just doesn’t matter very much.

So, what are the takeaways? First, our analysis helps us understand when coverage debiasing (aka the conformal guarantee) adds the most value. Both our plots and the math above suggest that the marginal conformal guarantee is most important when we are estimating an extreme quantile on a small hold-out set. Second, it shows us that the real contribution of split CP is in the score and the split. Data splitting is the key step that allows for \(\sqrt{n]\)-consistent

What about other tools that are built on top of split conformal prediction? The story is largely the same. Let’s first consider conformal risk control. For example, given a loss that is monotone in some parameter \(\lambda\), conformal risk control shows how to calibrate this parameter so that \(\E[\ell(f_\lambda(X_{n + 1}), Y_{n + 1})] \leq \alpha\).

Jackknife+/CV+

We’ve spent some time in the weeds studying the effects of coverage bias and variability of quantile estimates for a particular conformal method. Conformal prediction methods that achieve exact coverage on average, but do not guarantee small realized coverage deviations are not all that practical.

Let’s consider a problem in which I don’t have access to a hold-out set; in that case, the appropriate conformal method is known as full conformal prediction

Full conformal prediction

I want to thank Isaac Gibbs for our many hours of conversations about conformal prediction. I also want to acknowledge Tim Morrison, Anav Sood, Lenny Bronner, and Christine Yeh for helpful feedback on the writing of this post.